A week ago, in the first part of this tripartite story about serendipity in provenance research, I gave you some general information about the context of the accidental discovery I made.

On Thursday, July the 3rd, I continued my survey at the special collections of the University Library in Toruń. I decided to move from the manuscripts gathered at this library towards the regular analysis of the provenance marks left in the works by early modern chronographers and astronomers that are available at this particular library as I still have only a cursory knowledge of both the character of this collection and its ownership structure. As usual, I filled in a number of order slips and started to leaf through the subsequent volumes in hope of finding some early modern annotations.

Nothing unusual happened, the pages were clean as if they came freshly out of the printing press, until I received an awkward-looking cardboard box with multiple titles. It was not a regular book-block or sammelband as the brochures gathered under a series of consecutive shelfmarks were never bound together and were not even related to one another by a common subject or author. Apparently, the librarians gathered them together due to their relatively small size. What alerted me right after I opened the box was the fact that two titles with the lowest shelfmarks were actually missing. After a quick verification it turned out that two of the items which should be in the box were removed as they did not fit exactly into the box’s format and could be easily damaged.

The title I was looking for was one of minor works by Joseph Scaliger, i.e. his commentary to De tribus Judaeorum by Nicolaus Serarius, so I asked the librarian on duty to bring me this particular position. This, however, was not the end of the whole confusion as I wrote the cipher 5 in the Scaliger’s shelfmark in such a way that it was read as 6. Thus, by a pure accident, I received a completely different title and since it turned out to be a work of Johannes Kepler I decided to have a look at it.

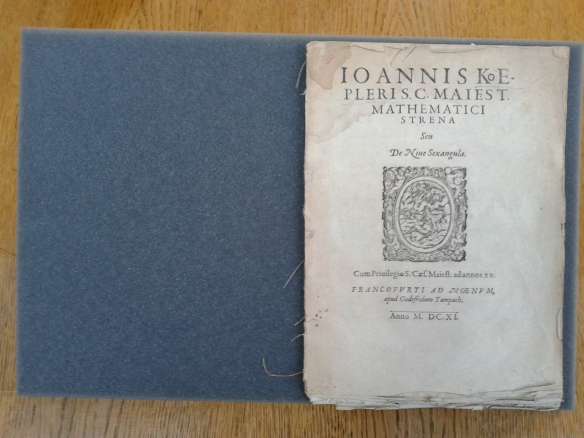

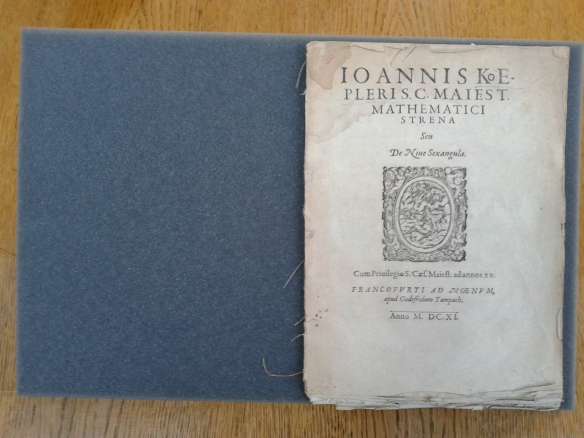

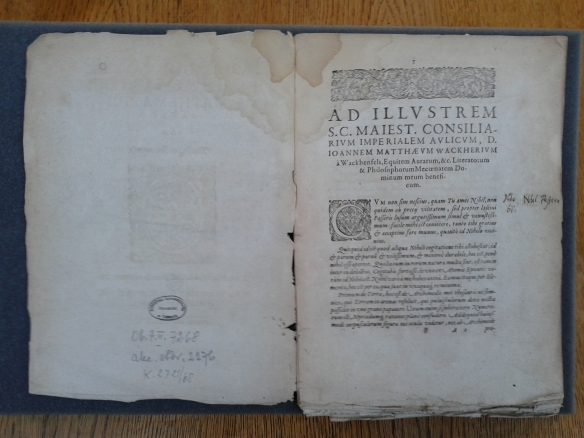

I opened the cardboard wallet and what I saw was a poorly preserved brochure without any binding but with damaged page edges and some occasional, light brown stains. It was the 1611 Frankfurt edition of Strena, a minor yet quite interesting work of Kepler’s.

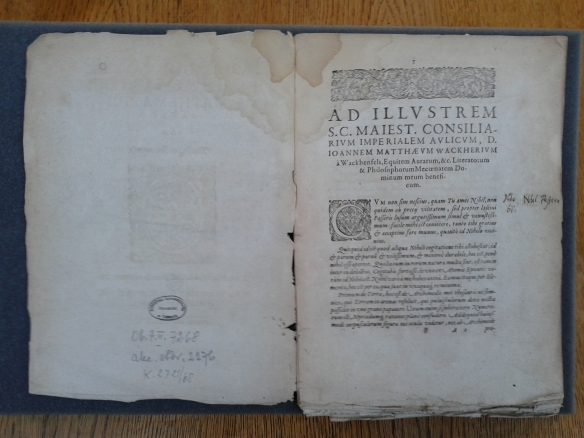

I never read it in the original until now but I knew it through it’s recent Polish translation. I turned the page carefully and what I saw on the margin of the next page (i.e. sig. A2r) made me to look around and make sure if I am actually sitting in the reading room at Toruń as the shape of the letters left next to the opening paragraph of Kepler’s dedicatory letter seemed oddly familiar.

I never read it in the original until now but I knew it through it’s recent Polish translation. I turned the page carefully and what I saw on the margin of the next page (i.e. sig. A2r) made me to look around and make sure if I am actually sitting in the reading room at Toruń as the shape of the letters left next to the opening paragraph of Kepler’s dedicatory letter seemed oddly familiar.

Five years ago, when I came to the Old Prints Department at the Jagiellonian Library and ordered my first book annotated by Broscius in order to prepare a paper for the Cracow workshop of the “Cultures of Knowledge” project, the librarian on duty opened the volume, had a look at some random pages and said that this was definitely his handwriting. Then I was ready to assume that being able to tell the difference between various early modern hands was a symptom of lunacy and that it was nearly impossible to give such a judgment after having just a quick glance at some minor scribble. After all these years, when I got accustomed to Broscius’s handwriting and transcribed hundreds, or maybe even thousands, of his words, including a rough draft of hist 1652 Apologia pro Aristotele et Euclide, I feel quite confident when I am asked whether it is his handwriting or not. Moreover, I can say that I fully understand the Cracow librarians and their level of familiarity with Broscius’s hand and I am actually ashamed of my past lack of belief. Although I still experience some difficulties with reading some parts of his manuscripts as some of them are blurred and some of them are simply so tiny it is really difficult to tell the difference between certain letters but despite that, I have the general idea of how he wrote particular letters, how he marked interesting passages, what types of ink or pencil he used, in which places of the book he used to leave notes, etc. and this knowledge, a classical example of learning by doing, substantially facilitates the process of verification of subsequent annotated volumes.

Five years ago, when I came to the Old Prints Department at the Jagiellonian Library and ordered my first book annotated by Broscius in order to prepare a paper for the Cracow workshop of the “Cultures of Knowledge” project, the librarian on duty opened the volume, had a look at some random pages and said that this was definitely his handwriting. Then I was ready to assume that being able to tell the difference between various early modern hands was a symptom of lunacy and that it was nearly impossible to give such a judgment after having just a quick glance at some minor scribble. After all these years, when I got accustomed to Broscius’s handwriting and transcribed hundreds, or maybe even thousands, of his words, including a rough draft of hist 1652 Apologia pro Aristotele et Euclide, I feel quite confident when I am asked whether it is his handwriting or not. Moreover, I can say that I fully understand the Cracow librarians and their level of familiarity with Broscius’s hand and I am actually ashamed of my past lack of belief. Although I still experience some difficulties with reading some parts of his manuscripts as some of them are blurred and some of them are simply so tiny it is really difficult to tell the difference between certain letters but despite that, I have the general idea of how he wrote particular letters, how he marked interesting passages, what types of ink or pencil he used, in which places of the book he used to leave notes, etc. and this knowledge, a classical example of learning by doing, substantially facilitates the process of verification of subsequent annotated volumes.

When I turned the page of the Toruń brochure I saw another annotation left in the margin of fol. A3r. This time it was in Polish and it read as follows: “Nie chuchay aby sie snieg nie rozpłynał”, “Don’t breathe on the snow as it will melt”, which is not an entirely meaningless comment if you take into consideration the fact that Kepler’s work was dedicated to the problem of the regularity of snowflakes and then I become absolutely sure that what I am looking at is in fact a working copy of Kepler’s Strena which belonged to Broscius!

Broscius’s marginalia in Polish are pretty rare as the majority of his annotations is in Latin. If one is looking for more notes in Polish, he or she should have a look at his diary I mentioned in the previous post. Latin or Polish, his annotations share one quality, which is an awkward combination of irony, sarcasm and maliciousness. However, the Polish commentary to Kepler is nothing in comparison to the Latin note Broscius left on the title page of another title which was bound together with Strena and which, along with few other positions constituted at some point a bigger book-block, now being broken with its parts dispersed (or lost). Here we have Broscius’s sacrasm in its pure form as he crossed out part of the title of Johann Remmelin’s work, providing it with a rather straightforward and laconic commentary:

Broscius’s marginalia in Polish are pretty rare as the majority of his annotations is in Latin. If one is looking for more notes in Polish, he or she should have a look at his diary I mentioned in the previous post. Latin or Polish, his annotations share one quality, which is an awkward combination of irony, sarcasm and maliciousness. However, the Polish commentary to Kepler is nothing in comparison to the Latin note Broscius left on the title page of another title which was bound together with Strena and which, along with few other positions constituted at some point a bigger book-block, now being broken with its parts dispersed (or lost). Here we have Broscius’s sacrasm in its pure form as he crossed out part of the title of Johann Remmelin’s work, providing it with a rather straightforward and laconic commentary:

Until the 3rd of July, I thought that I will always study Broscius’s manuscripts in the reading rooms at the 2nd floor of the Jagiellonian Library. This assumption turns to be false and the University Library in Toruń should be added to the list of libraries which have Broscius’s libri annotati. From the price tags attached to the final page of the volume and the year included in the acquisition number on the verso of Kepler’s title page, it appears that the volume was bought in one of the Dom Książki state-owned chain of antiquarian bookstores in 1968, althought it is not clear how these titles got into the antiquarian book market. It is highly possible that the works of Kepler and Remmelin dissapeared from the Jagiellonian Library in the 19th century and were included in one of the private collections. After the twentieth-century turmoil, these collections must have got dismantled and at least part of them found its way to the antiquarian bookshops and since the research questionnaire of the Toruń librarians was and is completely different from the one applied at the Jagiellonian Library, it is not a surprise that these annotations have escaped their attention.

Until the 3rd of July, I thought that I will always study Broscius’s manuscripts in the reading rooms at the 2nd floor of the Jagiellonian Library. This assumption turns to be false and the University Library in Toruń should be added to the list of libraries which have Broscius’s libri annotati. From the price tags attached to the final page of the volume and the year included in the acquisition number on the verso of Kepler’s title page, it appears that the volume was bought in one of the Dom Książki state-owned chain of antiquarian bookstores in 1968, althought it is not clear how these titles got into the antiquarian book market. It is highly possible that the works of Kepler and Remmelin dissapeared from the Jagiellonian Library in the 19th century and were included in one of the private collections. After the twentieth-century turmoil, these collections must have got dismantled and at least part of them found its way to the antiquarian bookshops and since the research questionnaire of the Toruń librarians was and is completely different from the one applied at the Jagiellonian Library, it is not a surprise that these annotations have escaped their attention.

However I am really happy about this accidental discovery, this is just the beginning of the actual research work. And since I made an observation that marginalia left by Broscius can provide some additional information about his scholarly workshop and the works he actually published, in the third and last part of this serendipitous cycle, to appear in a couple of days, I will make a preliminary attempt to explain the origin of marginalia in Kepler’s Strena.

However I am really happy about this accidental discovery, this is just the beginning of the actual research work. And since I made an observation that marginalia left by Broscius can provide some additional information about his scholarly workshop and the works he actually published, in the third and last part of this serendipitous cycle, to appear in a couple of days, I will make a preliminary attempt to explain the origin of marginalia in Kepler’s Strena.

Stay tuned if you wish to know why Broscius bothered with melting snow and how Kepler’s snowflakes are related to research carried out by the Cracow scholar.

T.B.C.

P.S.1. I wish to thank Dáibhí and Immo for inviting me to this conference and giving me the opportunity to share my research with this great audience, although the subject of my paper does not fit into the traditional timeframe of the conference (unless one decides that the Middle Ages ended up somewhere at the end of 17th c. …).

P.S.1. I wish to thank Dáibhí and Immo for inviting me to this conference and giving me the opportunity to share my research with this great audience, although the subject of my paper does not fit into the traditional timeframe of the conference (unless one decides that the Middle Ages ended up somewhere at the end of 17th c. …).