The yesterday’s post at Folger Library’s Collation brought back some memories of all the card catalogues I have studied back and forth over the past years, starting from the catalogue rooms of the Jagiellonian Library and the Czartoryski Library in Kraków through many other collections. I completely agree with Abbie Weinberg’s diagnosis and I also believe that the traditional card catalogue can be a powerful research tool which in some cases may prove to be much more useful or inspiring than its brand new, completely digital, glimmering online version and there are probably many other researchers who can confirm this. In this post, I would like to illustrate Abbie’s remarks with two catalogue anecdotes related to my own research.

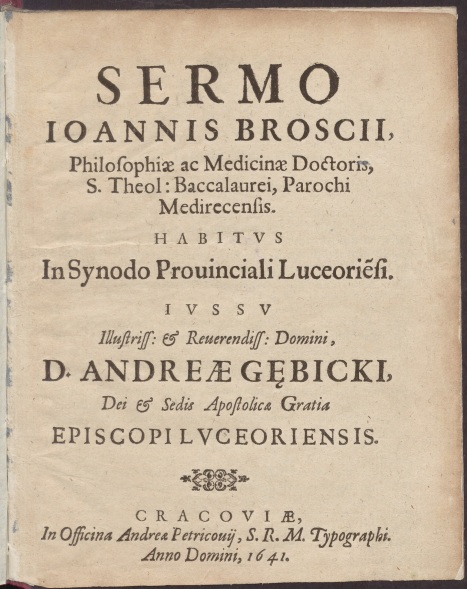

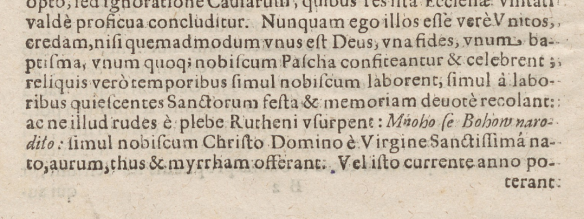

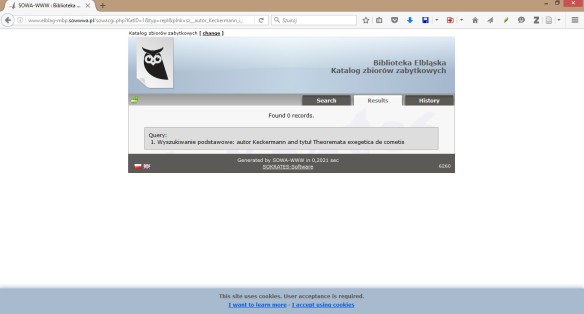

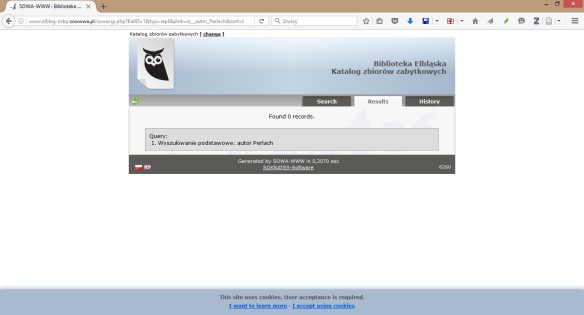

Last August, I visited the City Library in Elbląg (Elbing) hoping to find some annotated volumes that could show some forms of reception of early modern chronological controversies. Over the years I have developed a long check list of names and subjects which I try to verify methodically in almost every library I visit. When I was preparing for my trip to Elbląg, I checked their online catalogue, noted down all the shelfmarks that I needed and sent them in advance to the library so that at least some portion of the books would be waiting for me on Monday morning. On the first day I saw a trolley filled with volumes that I ordered and I was getting ready to have a look at them when the librarian instructed me that they have also some other volumes by the authors I am interested in. It turned out that the online catalogue does not provide full information about their holdings as there is a number of titles that can be found only in the traditional card catalogue. The reason for this lies in the fact that in the process of cataloguing of the special collections somebody made a decision to include ONLY the items that were bound as the first positions of Sammelbände and to skip other titles. If one would base her research only on the online catalogue and would never get in touch with the librarians she would never know that one of the composite volumes contains a brochure on comets by Bartholomew Keckermann with an dedication in author’s hand (call no. Pol.7.II.2419–2426) or to discover the heavily annotated collection of early sixteenth-century astronomical prints by Johannes Sacrobosco, Johannes de Glogovia and Andreas Perlach, followed by a set of notes by some anonymous sixteenth-century student (call no. Pol.6.II.211–216). Imagine that you are interested in preparing a census of Keckermann’s works in European libraries or you are chasing annotated copies of Perlach’s textbook that are scattered around the world (as Darin Hayton did in his magnificent recent study of astrology at the court of Maximilian I) – without the (unofficial) knowledge of discrepancies between the card and online catalogues and consulting the card catalogue (or asking the librarians to do this on your behalf) you would probably overlook a number of titles hidden deep in the stacks. In this case the analogue card catalogue remains the basic reservoir of knowledge about the full contents of the Elbląg collections – consulting the online catalogue may bring you results as the following:

(The necessity of consulting the card catalogues, either on site, or in digitized form or mediated by some incredibly patient librarian leads obviously to another issue, that is the limits of this kind of research and the criterion for saying stop at some point, but this is a topic I would like to keep for another occasion.)

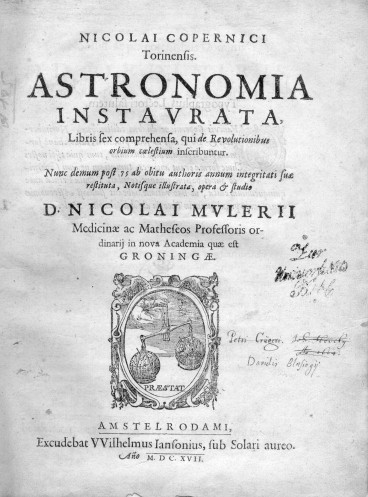

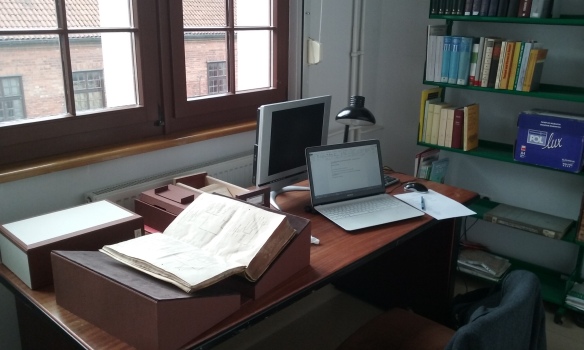

Another anecdote is related to my personal pursuit of books annotated and/or owned by Peter Crüger. As I explained in one of older posts, the biggest (and, historically speaking, natural) repository of Crüger’s books is the Gdańsk Library of the Polish Academy of Sciences, although a number of his libri annotati can be found in few other locations. In order to make sure that there are no other titles in Gdansk that could contain Crüger’s marginalia, I travelled there a number of times and spent ca. 20 working days browsing the traditional card catalogue and leafing hundreds of volumes. Yet doing one’s research in the special collections of the Gdansk Library is not that simple. Its card catalogue is a kind of a historical monument which documents efforts made by generations of German and Polish librarians who worked at this institution over the past two centuries, organizing its vast and rich holdings into thematic clusters and creating tools for finding volumes. This multigenerational nature of the catalogue makes it a unique material object in its own right. The drawers are filled with cards made of various kinds of paper, some of them very thin and fragile, some quite thick. The handwriting on the cards (I don’t recall seeing a single typewritten card!) is sometimes really awful so if you recognize your author but do not remember or do not know the title of his work, it is nearly impossible to decipher it and write down on the order slip. Once you get the author, title, year of publication and the shelfmark, it is good to check the latter against the subject catalogue which has the form of a series of monumental handwritten volumes and contains annotations by postwar librarians who left information about possible war losses. Between the card catalogue room and the bookshelf filled with tomes of the subject catalogue begins the real adventure as one needs to learn the whole system and begin to work his or her way through the collection. Although a catalogue, with its alphabetical order, clear system of shelfmarks and well-organized rows of cards put in drawers may seem to be a simple tool it has also some mysteries and secrets. For a majority of volumes that I saw in Gdansk (and, as I said, I saw quite a lot of them) this worked quite smoothly. But with time the system started to reveal some discrepancies that can be understood or explained only by a librarian who has a lot of experience in tracking down the volumes between the stacks. This is actually a matter of transmission of expert hermetic knowledge which cannot be learned in the university classrooms where the future librarians are trained but can be gained only through practice. During my last visit to Gdańsk, in early December 2015, I decided to have a look at the copies of Heinrich Pantaleon’s works. At some point I received two titles I have ordered (Chronographia Ecclesiae Christi of 1568 bound with works by Clemens Schubert, shelfmark Lb 1131 2o, and Martyrum historia of 1563 bound with the 1559 Basel edition of John Foxe’s Rerum in Ecclesia gestarum … pars prima, shelfmark Uph. fol. 116). Neither of them contained annotations in Crüger’s hand so I made some basic notes about the volumes and returned them quickly at the circulation desk. To my amazement, it turned out that there is a problem with another copy of Chronographia Ecclesiae Christianae (Basel: Nicolaus Brylinger, 1551) as the librarians cannot recognize the shelfmark (XX C fol. 252). First, they suspected that I miscopied the shelfmark, so we went to the card catalogue room, I showed the card and for the next two hours I could observe a number of Gdańsk librarians of various generations walking between the two catalogues and the stock, discussing the possible explanations of this problem. It turned out that nobody has ever seen this kind of shelfmark and that I accidentally digged up some archaeological layer of the catalogue which was completely forgotten. The most plausible explanation would be to assume that in the process of recataloguing of the collection somebody must have forgotten to change the shelfmark on the card or to prepare the new one and that this singularity is a kind of fossil documenting earlier stages of the development and organization of this collection. This, however, did not explain the fact that the subject catalogue did not contain references to this particular copy of Pantaleon’s work and, again, it is possible that it was lost either long before the introduction of the current system of shelfmarks (which is actually a work of German librarians inherited and maintained by their Polish successors) and hence the book never received the new shelfmark.

Although my desire to see the volume was never fulfilled, I learned an important lesson on different level: even such a prima facie simple tool as card catalogue requires interpretation and expert knowledge. This knowledge remains tacit and inactive for most of the time, but on special occasions like this missing copy of Pantaleon, has to be activated and this is only possible thanks to the transmission of knowledge from one generation to another. And just like old books, catalogues sometimes also require an archaeological approach and toolbox.