It’s time for a quick recapitulation of my last week’s visit to Gdańsk Library of the Polish Academy of Sciences. I was going there in high spirits as I was hoping to find at least one or two more volumes annotated by Peter Crüger. What I found instead was a large pile of books that were never actually read (or, at least some of them, were read but not in a very active way). My chase for Crüger’s marginalia slowed down a bit and I felt like my protagonist, when he took his copy of Petavius’s De doctrina temporum and jotted down in his microscopic hand that “he paged through the entire book 1 of Clement of Alexandria’s Stromata a couple of times” (ibi horum plane nihil aliq[uo]ties p[er]volvi totum librum I) but he failed to find the original passage to which Petavius had made a reference to. I console myself that this kind of despair might be temporary and that there may be still some volumes that contain Crüger’s annotations. The output of the last week’s survey, however, is mostly negative.

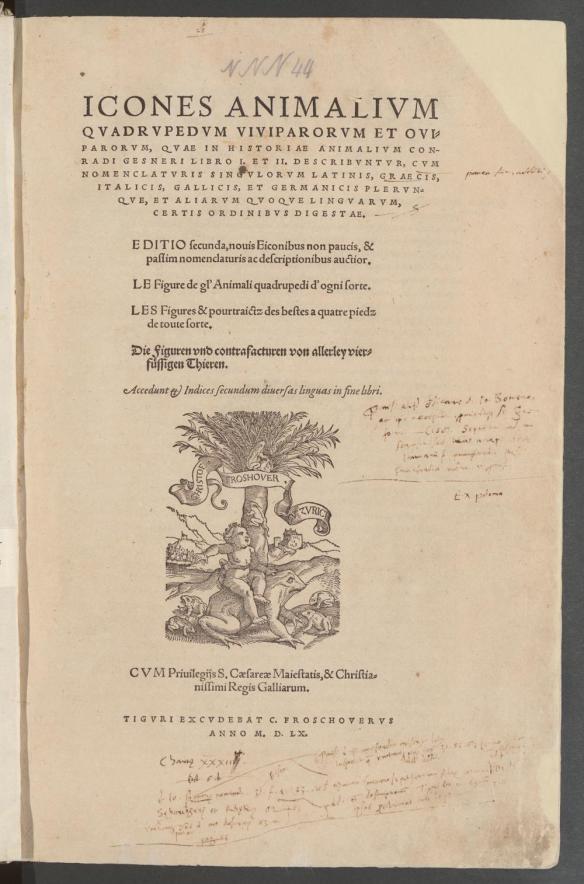

I have compiled a list of authors and works to which Crüger’s annotations. Some of them are quite precise, like his reference to Simplicius’s commentary to Aristotle’s On heaven (Venice 1526 edition, in folio) so if the catalogue does not show any records of such edition I decided not to order any other copies, at least for now. But some of his references are less precise and thus call for massive orders and may lead one eventually to insanity. Sometimes he just compares his own copy with the edition cited by, let’s say Petavius or Scaliger, but provides only a note that the text in question is on a different page (“mihi pag. XYZ”), sometimes he just mentions a title. It is ok, if he quotes works that had two or three editions and two or three copies are actually in the library. But when it comes to such authors as Livy, published a number of times and in all possible formats – it can have devastating consequences for researcher’s psyche, physical condition of the librarian responsible for taking the books from the shelves, and can eventually lead to the significant deterioration of mutual relations of both sides of the reference desk. I have filled in an endless number of order slips and paged through a large number of volumes, just to find out in the end that only one of them bears annotations made by hand that resembles the one of Crüger but even in this case I cannot be sure. That’s the other side of the coin: finding out that some of the volumes were never read or if they were, they belonged not to the people we are interested in, at least at this particular moment.

As for me, I still think I could be perfectly happy with the rich corpus of Crüger’s annotations I have gathered in Gdańsk, Berlin and Frombork – they are consistent, thorough, some of them are pretty extensive and if I only manage to interpret them in a proper way, they can shed some light on his reading techniques (on the history-of-reading level) and the way he found his way into the middle of calendrical and chronological controversy (on the scholarly level). But despite this, I still nurture a kind of hope that some day I will dig up a volume annotated by Crüger that will not belong to the corpus of astronomical, historical and chronological texts and will help me, for instance, in answering such questions as how did he read literary works. Right now, the method based on massive orders and compiling a long check list of names failed. This makes me wonder whether it would make sense to get back to Gdańsk in order to check another pile of volumes based on Crüger’s remarks and whether this method is worth following at all. Perhaps some other marginalia lovers who happen to read this blog will help me in solving this methodological issue – at the moment I feel as if I had a box of tasty cookies (i.e. identified books with annotations) and I am not sure whether it is good to abandon them in search for the mythical “cake” (that is, a further reconstruction of the library). Any suggestions will be most welcome!

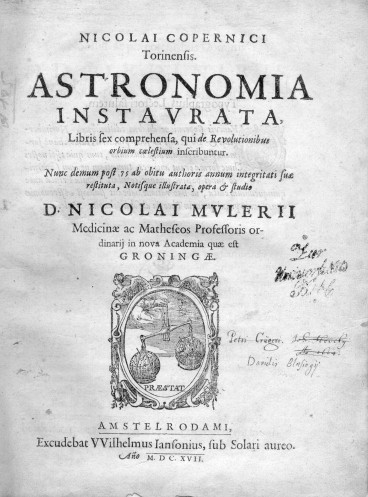

Finally, the reason for this failure may lie not in the fact that these books did not survive. They could simply survive somewhere else. Collections were dispersed, scattered, moved, sold out, stolen and the fact that, for instance, Hevelius used some of Crüger’s books and bought them on the second hand market after his own library and observatory got burned down proves to the fact that not all Crügeriana found their way to the library of the Senate of Gdańsk. One of Crüger’s volumes, the 2nd edition of Copernicus, is held in Moscow; one of his volumes was also identified at the Library of the Observatoire de Paris, the next two are in Potsdam and Frombork. So, perhaps, it is high time to follow the example set by Kees-Jan Schilt in his own quest for Newton’s libri annotati: if you are a special collections librarian or a student of early modern annotations, especially those left in astronomical works, and you think that you might have seen a book annotated by Crüger, do let me know at michal.choptiany[at]al.uw.edu.pl! Although books owned and/or used by Crüger do not have such easily identifiable features as those owned and/or used by Newton, I will be happy to share a set of samples of his handwriting and give more precise information about the way his hand can be identified.

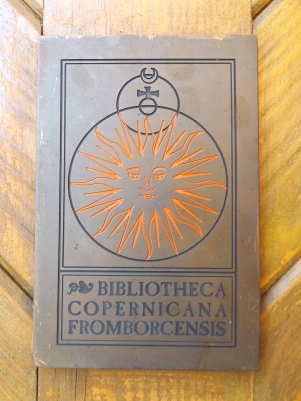

Title page of Crüger’s copy of Copernicus’s Astronomia Instaurata; Frombork, Nicolaus Copernicus Museum, shelfmark MF/SD/321