Prophecies were ‘bestsellers’ not only in the Middle Ages but also in early modernity. More than year ago I started to work on a commentary to the edition of the manuscript copy of Jan Latosz’s Przestroga (A Warning), the only surviving witness to this astrological and chronological dissertation published in Cracow in 1595. At some point I had to postpone my work as I encountered a puzzling passage which required some time to solve it.

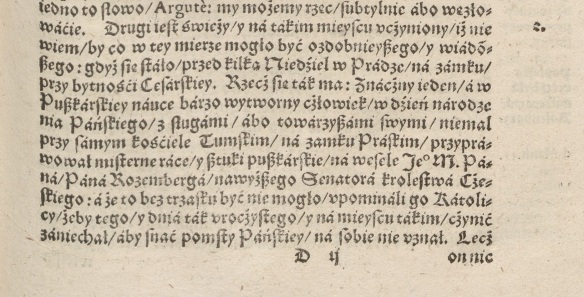

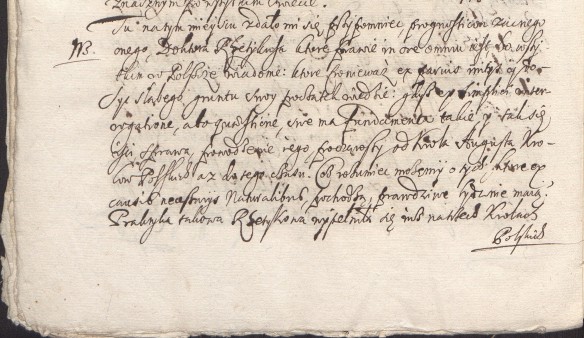

Tu na tym miejscu zdało mi się przypomnieć prognosticon zacnego onego Doktora Rhetykusa, które prawie in ore omniu[m] jest, bo wszytkim w Polszcze wiadome, które ponieważ ex parvis initiis i dosyć słabego gruntu swój początek wiedzie, gdyż ex simplici interrogatione, a to quaestione swe ma fundamenta takie i tak się iści sprawa, powodzenie jego, począwszy od króla Augusta, królów polskich aż do tego czasu. Cóż rozumieć możemy o tych, które ex causis necessariis naturalibus pochodzą? Prawdziwe być nie mają? Praktyka takowa Retykowa wypełniła się już na trzech królach polskich …

It happened to me here to remind about the prognostication of the good Doctor Rheticus, which is on everyone’s lips and is known to everyone in Poland. Although its origins and ground are modest and weak as it is a result of simple interrogation, it has some foundations and the fates of the kings of Poland starting from the king [Sigismundus] Augustus [predicted in it] happen to fulfil. What should we understand, then, about those which come from the necessary natural causes? Should they be considered true? The Rheticus’s practice has already came true for three Polish kings …

Latosz’s reference to Rheticus in a 17th-century manuscript copy of his Przestroga of 1595 (MS Warsaw, National Library, 6631 III, fol. 20v, fragment; source: Polona)

In the next sentence Latosz provided brief characteristics of the first three elective kings of Poland, Henri de Valois, Stephen Báthory and Sigismund III Vasa so it seemed that my astrologer was actually paraphrasing a text known back then as a work of Rheticus. The first book I turned to to check this was Ludwik Aleksander Birkenmajer’s monumental study on Nicolaus Copernicus which is a real treasure trove of Copernicus- and Rheticus-related archival bits and pieces. It turned out that indeed, there is something like Rheticus prognostication on the elective monarchs but the text edited by Birkenmajer and taken from a manuscript miscellany held at the Jagiellonian Library in Cracow seemed to be slightly different from the one Latosz referred to as the latter gave descriptions in different order. Birkenmajer mentioned that there are also some other copies of Rheticus text which are located, among others, in the Ossolineum Library (now divided between Wrocław and Lviv) and in Vatican so I decided to take this lead. Unfortunately, consulting the scans from these libraries made it even worse as these copies also seemed to be substantially different from the samples given by Latosz in 1590s and by Birkenmajer in 1900.

First, I thought it was just a mere accident but then I referred to Karl-Heinz Burmeister’s three-volume thorough account of Rheticus’s biography and works and it turned out that things were even more complicated than I initially thought. Not only these few manuscripts mentioned by Birkenmajer turned out to be merely a drop in the bucket of the corpus of witnesses to Rheticus text but, as it turned out, they had very little in common with the text Burmeister published as the prognostication on the kings of Poland. The piece published by Birkenmajer and those I found in Ossolineum in Wrocław and in Stefanyk National Scientific Library of Ukraine in Lviv were rather laconic in comparison to the elaborate horoscope edited by Burmeister.

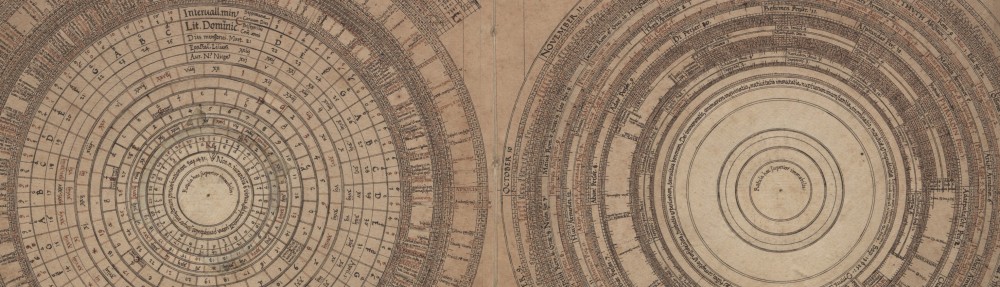

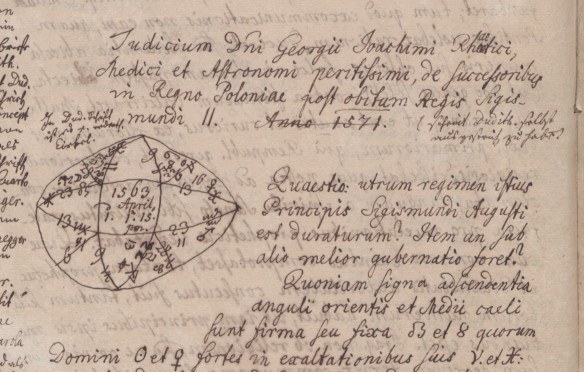

Soon I came to realize that all scholars who were referring to Rheticus’s prognostication over the past hundred years were playing a blind man’s buff. Every one of them, after seeing few manuscripts, took for granted that the other copies were pretty much alike so if someone examined a late seventeenth-century simplified copy consisting of schematic list of kings he or she simply assumed that other witnesses, known from catalogue descriptions, are exactly the same. I also suppose that even Burmeister himself did not bother to consult all the manuscripts he included on his list of witnesses as some of the copies from Gdansk were considered lost at the moment when he published his study. However, in one thing Burmeister was right, i.e. in giving the privileged position to the manuscript that is now located in the University Library in Wrocław and which provides the most plausible version of Rheticus’s text. Unlike many other manuscripts related to this prognostication, it contains elements of astrological apparatus, including the precise time for which the horoscope was erected as well as an astrological diagram showing the positions of planets at the moment of interrogation. All these elements together with the elaborate characteristics of kings make it look like a work of a genuine sixteenth-century astrologer. The only tiny problem related to this manuscript is the fact that it comes from the eighteenth, not the sixteenth century…

The most reliable witness to Rheticus’s horoscope – MS Wrocław, University Library, Akc. 1949/594, fol. 56v, fragment

As much as I wanted to believe that Burmeister made the right choice, there were still few question that required some answers. Why should we believe that the 18th-century manuscript should be treated as a key witness to the tradition of text dating back to the second half ot the 16th century? What happened to the Rheticus’s autograph? What are the origins of the prognostication as such? Is it possible to reconstruct the process of textual transmission from the Wrocław MS to the dwarfed copies I saw at the beginning of my investigation? Finally, what about other texts that appear to be somehow linked to Wrocław MS but their form does not resemble even the dwarfed, simplified copies?

While I have no idea what happened to Rheticus’s autograph the answer to the question about the origin of the Wrocław MS and the prophecy as such seems to be quite plausible. The manuscript used by Burmeister is an 18th-century copy of papers of Andreas Dudithius, Catholic bishop, Antitrinitarian and diplomat in the service of Maximilian II. The original papers were lost at some point but before this happened some local historian aware of the importance of Dudith copied them and surrounded with some factual annotations. As to Dudith himself, his connections with Rheticus are quite well documented. Their paths have crossed in Cracow when the first served as imperial envoy and intelligencer and the latter pursued his career of physician and astrologer and got close to the local centres of power. During their stay in Cracow, Dudith has created a circle of erudites interested in astronomy and Rheticus was one of its members. It is quite possible, then, that Dudith was one of the first readers of the horoscope. Although, as Gábor Almási has shown, Dudith was not very much keen on astrology – in fact, he was rather sceptical about it – he was an experienced politician, so it is also possible that he was the actual originator of the whole astrological enterprise or that he quickly incorporated it into his own political and diplomatic agenda. Even if he wasn’t behind the creation of the horoscope and the prognostication was either made of pure curiosity or commissioned by the royal court, it is quite reasonable to assume that Dudith played a significant role in disseminating the text by means of correspondence and there are some fragments in letters to and from him that clearly show that he introduced some astrological pieces into the Central European information exchange network. Being a representative of the Habsburg emperor in the capital of a country which was about to experience a political change, Dudith must have fell back on all possible means to win favor of Polish nobility and secure the election of the Habsburg candidate to the Polish throne.

As my interest in the history behind the Rheticus’s prognostication grew bigger, I kept looking for some other witnesses to this text and started consulting them, either in person or by means of microfilms and digital copies. Soon it turned out that some of them generally confirm the contents of the Wrocław MS although none of them contained the astrological chart and their astrological layer was heavily corrupted. In the meantime, the pool of manuscripts started to reveal some other curious aspects. For instance, soon it turned out that the prognostication was translated not only into German, what has been noted by Burmeister, but also into Polish and while the German version, most likely linked to the city of Gdansk, was consistent in all copies, the Polish had few very distant variants.

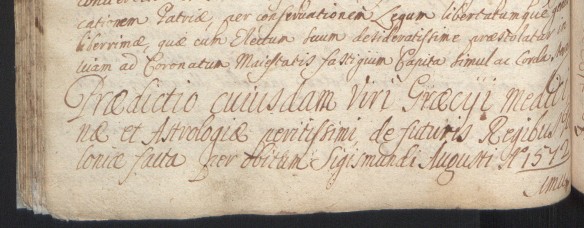

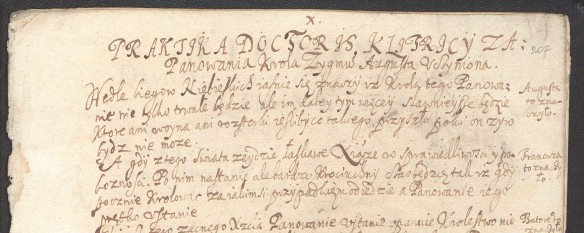

The analysis of these texts did not allow me to reconstruct the precise devolution of the text, from the inextant archetype (substituted by the Wrocław MS) to the most corrupted versions – there were simply too many differences between them to decide which one should be superior to another, especially if they all come from the second half of the seventeenth century and from different locations. The process of collecting all witnesses allowed me instead to do other thing, i.e. to analyse the process of condensation of the original horoscope into the form of a popular prophecy which had very little to do with the text that was authored by the disciple of Copernicus. One of the aspects of this process was the simplification of the text: first, the astrological apparatus was abandoned, then some of the characteristics got abridged, and the latest versions of the prophecy, although their titles still echoed the original horoscope, consisted merely of a list of two- or three-word characteristics of future kings of Poland. Another aspect is the fading memory of Rheticus as the author of the horoscope or, as you like, the elective prophecy. Latosz was able to refer to the author of Relatio prima thanks to the fact he was well aware of the astrological traditions of Cracow and he did this in 1590s, only two decades after Rheticus’s death. But these details must have fell into oblivion or simply seemed irrelevant to the members of nobility who continued to copy this text into their miscellanies until early eighteenth century. When one takes a look at all versions of the title she will immediately notice a long parade of names that have very little to do with Rheticus and one of the late 17th-century copies of the heavily abridged Latin text of the prophecy names ‘some Greek’ as the author, while another copy mentions ‘Doctor Clitricius”. There is some wisdom in it as, up to a point, ‘Rhetici’ and ‘Graecii’ or ‘Clitricii’ sound alike, but this manuscript, like many others, shows that the general astrological provenance of the text and the aura of secret knowledge were much more important to the users of this text than the actual identity of its author.

Rheticus disguised as a Greek in MS Warsaw, National Library, 6647 II, fol. 267v, fragment; source: Polona

Rheticus as ‘Doctor Klitricius’ in the Polish version of the prophecy, MS Warsaw, National Library, 6634 III, fol. 207r, fragment; source: Polona

What is the reason, one might ask, why we should beware the Rheticus’s prophecy? Since the expiry date for this horoscope expired long ago there is nothing to worry about on the astrological level, yet on the scholarly one there is. It is a common problem for all scholars who are trying to stabilize the text to decide when to cease their pursuit of further copies, especially if there is no central manuscript. In result of my chase I managed to collate the Wrocław MS with other witnesses to the longest version of the horoscope, complicating thus basic edition created by Burmeister. I also edited some variants of this text that document other stages of its degeneration and language versions. And in general I feel that the results of my toils are legible and shed some critical light on the to date claims about the Rheticus’s text. Yet, even now, when my two articles on the topic – one discussing the origins of the horoscope and the Dudith’s involvement, the other focused on the manuscript tradition – have been sent to the press and will appear later this year, I keep thinking about other possible copies of the prophepcy that should have been included but I was not aware of their existence. So even if there is nothing baleful in the horoscope as such, studying it may lead to a kind of textual anxiety which may urge one to check compulsively manuscript catalogues in hope of tracing another witness to the text and to keep leafing through hundreds of pages of uncatalogued manuscript miscellanies in search of just one more copy of this incredibly popular text.