When one is writing about historical issues related to Christmas, it is quite natural to include something about the nature of the star of Bethlehem, chronology of the life of Jesus or the development of the very feast of Nativity and ancient and modern controversies related to it. While I do believe all these issues are fascinating, it is sometimes good to find some other Christmas-related topic. One of them can be found in a sixteenth-century Polish text.

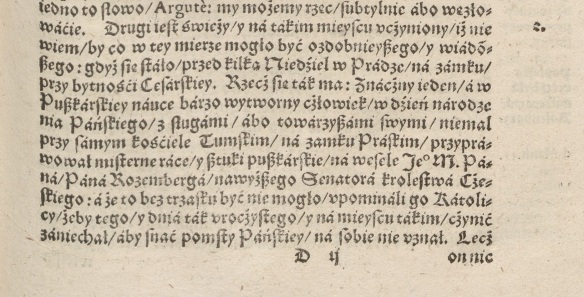

The polemical writings related to the introduction of Gregorian calendar took different rhetorical forms: some of them were written as satirical dialogues, some of them pretended learned treatises (although their authors were far from being learned), finally some of them hidden the polemical content under the costume of good old sermon. One of such works is a calendrical bestseller, Two sermons on the calendar reform (O poprawie kalendarza kazanie dwoje, 1587) by Stanislaw Grodzicki SJ, which was published three times within the period of two years and is actually one of the most sophisticated and elaborate texts that were produced during this interconfessional exchange. Grodzicki was a well-trained preacher and althought it is not quite sure whether his written ‘sermons’ reflect exactly the sermons he delivered in person (probably not), it is quite striking that he mastered a substantial number of rhetorical devices and knew very well how to tie them together in order to create a convincing rhetorical structure.

Today I will spare you the details of Grodzicki’s argumentation and will keep them for some other occasion but I thought that one exemplum introduced by the Polish Jesuit is worth mentioning on the first day of Christmas (although I must warn you it is quite horrifying!)

The other example is more recent and of such nature that I can hardly imagine something more relevant. It is related to events which took place a couple weeks ago at the Prague Castle during the Emperor’s stay. On the Day of Nativity a certain important man who was well-experienced in the fireworks craft took his servants or companions and launched his maroons and fireworks by the very walls of the cathedral church in order to celebrate the wedding of his Master, Lord Rosenberg, the highest senator of the Bohemian Crown. And since it was impossible to perform this show without any noise, the Catholics reprimanded him not to do this on such a solemn day and occasion in order not to incur Lord’s anger. But he did not care about these admonitions, made laugh of them and said that he did not care about the corrected calendar and he wanted to celebrate the feast according to the old one. By the mysterious act of mighty God few hours later the gunpowder caught fire, made a great noise and thunder, and burnt severely both the master and his servants. The neighbours have gathered immediately and saw figures looking more like devils than men, half-alive, taken straight from the fire, confessing their sins, talking about God’s miracle and asking for a confessor. The latter, when he finally arrived, had listened to the confessions of all three men who renounced their heresy and recognized one Roman Catholic Church. The priest absolved them from heresy and other sins and, following the Catholic tradition, gave them the sacrament of our Lord’s body. After two hours from accepting the Holy Sacrament two comrades rendered up their souls to God and so did their master few hours later at dawn. Thus our Lord Jesus Christ by means of, so to say, one sermon of brimstone fire converted three souls and at the same time confirmed his decision announced through the hands of his Vicar and showed his grace to Catholics by saving the Prague cathedral and castle from the danger of fire.

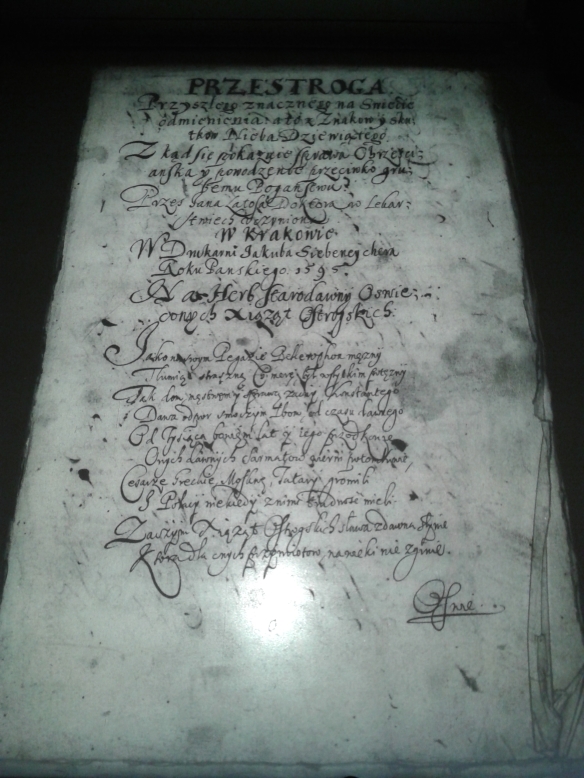

Detail of p. 25 of the 3rd edition of S. Grodzicki’s Two Sermons on Calendar Reform

(Vilnius 1589)

Grodzicki’s Sermons will become a part of the critical edition of polemical writings I have been working on for the past ten or fifteen months. The book will appear in Polish at some point but before I send the final manuscript to the publisher, I need to explain few stories as the one above. If you happen to know any late sixteenth-century texts that could serve the Polish priest as a source for his explosive exemplum, do let me know! (While the main protagonists like Rudolf II or William of Rosenberg are quite easy to identify, the main source of the anectode remains unknown – at least for me.) Also, if you know any other calendar reform-related miracula (both those confirming the rightness of Gregorian calendar, like the one above, or those showing its unquestionable fallaciousness), please let me know – it would be fascinating to know how many stories like these were spread throughout Europe in order to prevent people from falling into one of two main calendrical heresies.

Meanwhile, I wish you a happy festive season (regardless of calendar system you may use). Stay tuned for more news about the project – these should arrive in early January.