Last December, when I carried out phase I of my preliminary survey in the tremendous special collections of the Gdańsk Library of the Polish Academy of Sciences my dreams of a marginalia fetishist came true once again. It turned out that my hopes of finding Central European scholars annotating works on calendars and chronology and polemicizing with Scaliger, Clavius, Petavius, Calvisius et consortes by means of annotations left on the pages of their books won’t be limited to the (rich enough) set of glosses left by Joannes Broscius and a bundle of anonymous libri annotati found here and there but will be expanded by at least one more reader who can be identified and whose annotations can be linked with his own works. This is the case of Peter Crüger (1580-1639), professor of astronomy and poetics in the Gymnasium Academicum in Gdańsk, one of the three famous Lutheran educational centers in the broadly understood Pomerania region.

Gdańsk Library is well-known as a treasure trove of various unique primary sources to the intellectual history of the region and its institutions and it seems that even after many years of scholarly efforts there are materials that have never been studied closely or have been studied for wrong reasons. This is the case of Crüger, whose annotations, mostly those left in the 3rd edition of Copernicus’s De revolutionibus (now preserved in the Copernicus Museum in Frombork) attracted attention of scholars not due to the fact that he was an scholar in his own right, but mostly because he was a teacher of a much greater mind, i.e. Johannes Hevelius. This attitude can be best observed in a 3-pages long article published ca. 70 years ago by Tadeusz Przypkowski. In it, Przypkowski presented Crüger’s annotations in his copy of the 3rd edition of De revolutionibus but the conclusion he drew is somewhat surprising as he postulated creation of a monograph of Hevelius! It seems that only Owen Gingerich, in his Census of the first and second edition of Copernicus’s groundbreaking work did Crüger justice, presenting him as an actual reader and giving a very concise yet instructive report on the contents of his marginalia in one of the Moscow copies of De revolutionibus.

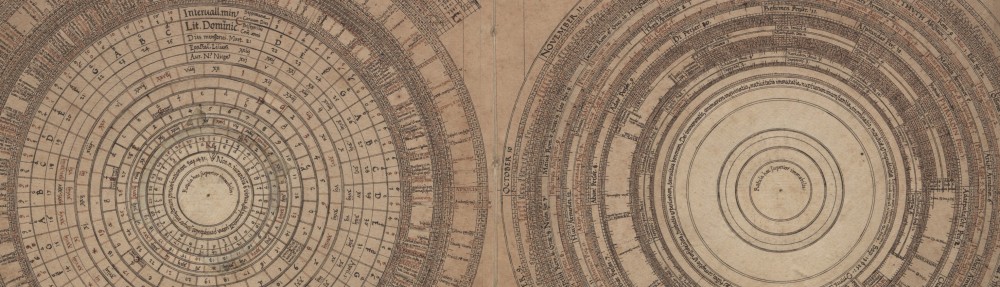

Title page of Astronomia instaurata (so-called 3rd edition of Copernicus’s De revolutionibus), owned in turn by Peter Crüger and Johannes Hevelius; Nicolaus Copernicus Museum, Frombork, Poland

Apart from these two volumes, notes in Crüger’s hand seem to be a virgin land and I am going to explore it a little bit, starting from the calendrical and chronological corner yet I guess there may be also some other areas that turn out worth exploring.

My December visit to Gdańsk proved to be only a beginning of a longer journey. After studying few books annotated by Crüger it turned out that one of them is preserved in quite a surprising location:

My March trip to the 2015 Annual Meeting in Berlin, where I organized a series of panels on chronology in the early modern period, seemed to be an excellent occasion to have a look at this volume. On Wednesday before the official proceedings of the RSA began, I spent a lovely morning at the Library of the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics in Potsdam-Babelsberg where a copy of Kepler’s Astronomia nova, owned in turn by Crüger and Hevelius, is preserved. It is a fine volume which was carefully restored in 1950’s and all the annotations except for few minor ones have survived until today in highly legible form. I am really happy for two reasons: this brief, technical visit allowed me to pick up a single yet quite substantial piece of a puzzle which can be somehow linked to the astronomical workshop of Crüger and at the same time, like all good marginalia (should) do, opens up new paths for further queries.

Two days after my visit to Postdam and just seconds after the chronological panels, a bucket of cold water was poured on my head. I went to the roundtable session celebrating the 25th anniversary of Anthony Grafton and Lisa Jardine’s seminal essay on Gabriel Harvey’s reading of Livy. One of the most important things I learned during this fabulous meeting is that Grafton and Jardine, calling themselves “granpa and grandma of marginalia studies”, are not satisfied with the way their article was applied and imitated in further studies on early modern readers and that they ment something different than establishing a simple generative model for writing an endless series of papers on ‘X reading Y‘. While I believe every case is different and it always depends on the skills and approach of particular historian what s/he will eventually do with such kind of primary sources as marginalia, I must admit that Grafton and Jardine diagnosed an important illness (or a sin) of letting oneself believe that finding a reader and his annotations is a sufficient condition to write yet another study following the rules established by their 1990 paper. I have spent few past years with annotations, either doing research for my PhD, then moving on to other fields, and it was last December when the symptoms of this illness (or inclination towards this sin) struck me for the first time. It was then when I saw Crüger’s annotations for the first time during my visit to Gdansk: they simply triggered a feeling of finding something familiar yet new, something that you dealt with earlier and you know how to proceed with this kind of sources (or at least you believe you know) and at the same time something idiomatic and unique, which will force you to find new way of writing on this kind of sources even if you feel OK with the way you wrote your earlier studies. This feeling of familiarity can be misleading and cannot end well and it always takes great effort to overcome one’s mental and scholarly habits in order to find new approach and I think the apparent ease with which the “Studied for Action” paper can be emulated is the main fault for the entire confusion about the method and purpose of studying marginalia.

Certainly, there are some aspects of early modern annotations that can be treated as basis for data-mining and large scale analysis based on a large corpora of libri annotati – this is mostly the purpose of a new exciting project on the “Archaeology of Reading” with Grafton and Jardine as principal co-investigators. I really look forward to the development of this enterprise and I can only imagine what kind of tools and results the project will bring over the years to come. Yet, being also an admirer of micro-narratives, I do not want to let early modern readers dissolve in the pool of hundreds and thousands of annotations. I am not sure if the authors of the paper celebrated in Berlin would agree with me that what makes the set of marginalia writing about is the fact that they allow one to go beyond the closed cycle of references between a series of books and look at the relationship between these annotations and some other kinds of evidence. It is really difficult to find such a link in some cases, sometimes it is not necessary – it depends on the kind of history you would like to write and how far your sources and your imagination can take you. And I believe that this fact gives me at least partial absolution: “my” readers were involved in public activity, both as teachers and polemicists, and even if large chunks of their annotations have a technical or theoretical character and create a coherent system of internal references between piles of books, some of them still extant, some of them perished, they can be linked to their involvement in the public sphere where they translated their professional knowledge into the more popular kind of discourse and tried to shape views of citizens without professional training in calendrical astronomy or training of any other kind.

Having said this, I must confess that my sin drove me again to Gdańsk where I arrived yesterday and will stay until Friday, carrying out phase II of my survey. Here I am, an irredeemable sinner, willing to study marginalia in hope that there is some kind of order that can be derived out of them and that they can create pieces of narrative that can be written on Crüger – not as an isolated scholarly reader but as a scholar who by means of reading and linking various texts laid foundation for education of next generations of citizens of Gdansk/Danzig and whose knowledge of astronomy and the way it can be applied to chronology allowed him to get involved into public debate on Gregorian calendar and use chronology as a vehicle for other kinds of knowledge. Having transcribed a large portion of Crüger’s notes today and awaiting to see some other of his volumes over the next four days, I am still thinking about differences and similarities between him and other readers I have studied or read about. When you are sitting in a reading room, trying to decipher Crüger’s tiny hand, focusing on direct relations between the note left in the margin and printed text, trying to figure out the real meaning of all these references to Josephus, Bucholzer, Tremellius, Scaliger, Casaubon, Kepler and Petavius – it is easy to forget about the reality outside the library. Bu the world behind the library’s walls does exist, just as it did in Crüger’s times – and this is probably one of the arguments which gives some value added to the study of annotations and makes this kind of scholarship useful not only for book historians and manuscript fetishists but also for people interested in social interactions and the history of shaping of public sphere through of education, scholarship, and debate.